The NADA Story

1917: Dealers Launch a National Association

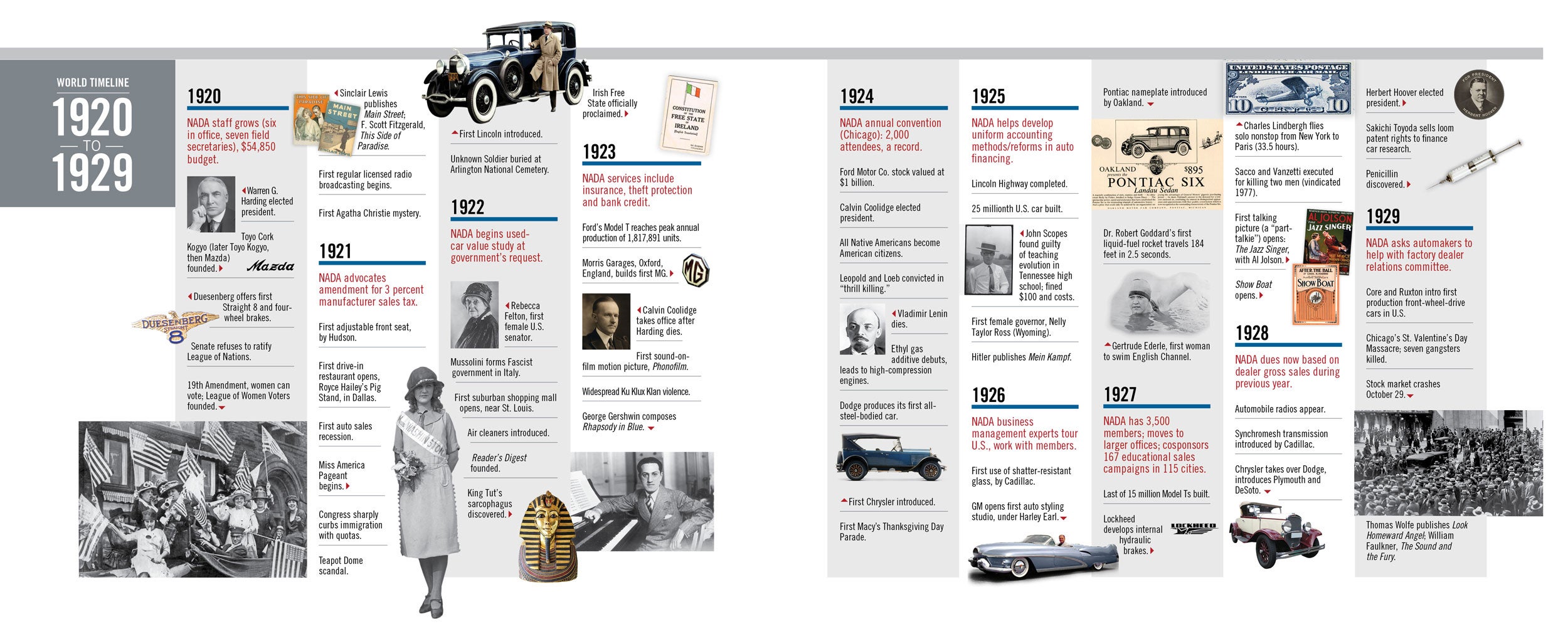

NADA was born in 1917 when a group of dealers set out to change the way Congress viewed automobiles. Thirty dealers from state and local associations went to Washington and set up base at the Willard Hotel. By convincing Congress that cars weren’t luxuries as they had been classified, but were vital to the economy, the group prevented total factory conversion to wartime work and succeeded in reducing a proposed 5 percent luxury tax to 3 percent.

These businessmen realized that the nation’s 15,000 dealers needed continuing representation in Washington. Two months later—on July 17 and 18—130 dealers met in Chicago to elect officers. Milwaukee dealer George W. Browne was the first NADA president. To launch the association cost exactly $102.71, which covered mostly telegrams, telephone calls and postage.

The Early Years

The annual convention was an NADA fixture from the beginning. The association wanted its meetings to coincide with auto shows because of all the dealers attending. So, before it was six months old, NADA held its first annual meeting, with 138 delegates, during the Chicago Auto Show. St. Louis was chosen as the city for NADA headquarters.

The first important national legislation sponsored by NADA was the National Motor Vehicle Theft Law (the Dyer Act) in 1919, which made it a federal offense to steal a vehicle and take it across state lines. NADA also promoted uniform accounting methods among dealers and was active in seeking auto financing reforms.

By 1920, NADA office staff had grown to six people, with seven field secretaries. The annual budget was $54,850. Member services were expanded to include insurance protection and bank credit. The 1924 convention in Chicago had 2,000 attendees.

In 1922, NADA began to study used-car values as a service to members. A decade later those studies became the N.A.D.A. Official Used Car Guide, carrying the U.S. government’s endorsement as the nation’s authority on used-car prices. About 40,000 copies were printed and mailed to subscribers in December 1933. The first issue was 388 pages, published for 21 regions.

Interest in used-car values was high for two reasons. One, after debating for years how to handle trade-ins, dealers finally began applying trade-in values toward new-car down payments. Two, used cars outsold new cars. At the end of World War I, sales of used cars were about half as numerous as new-car sales. But from the 1920s through the 1950s, used-car sales consistently exceeded franchised new-car sales.

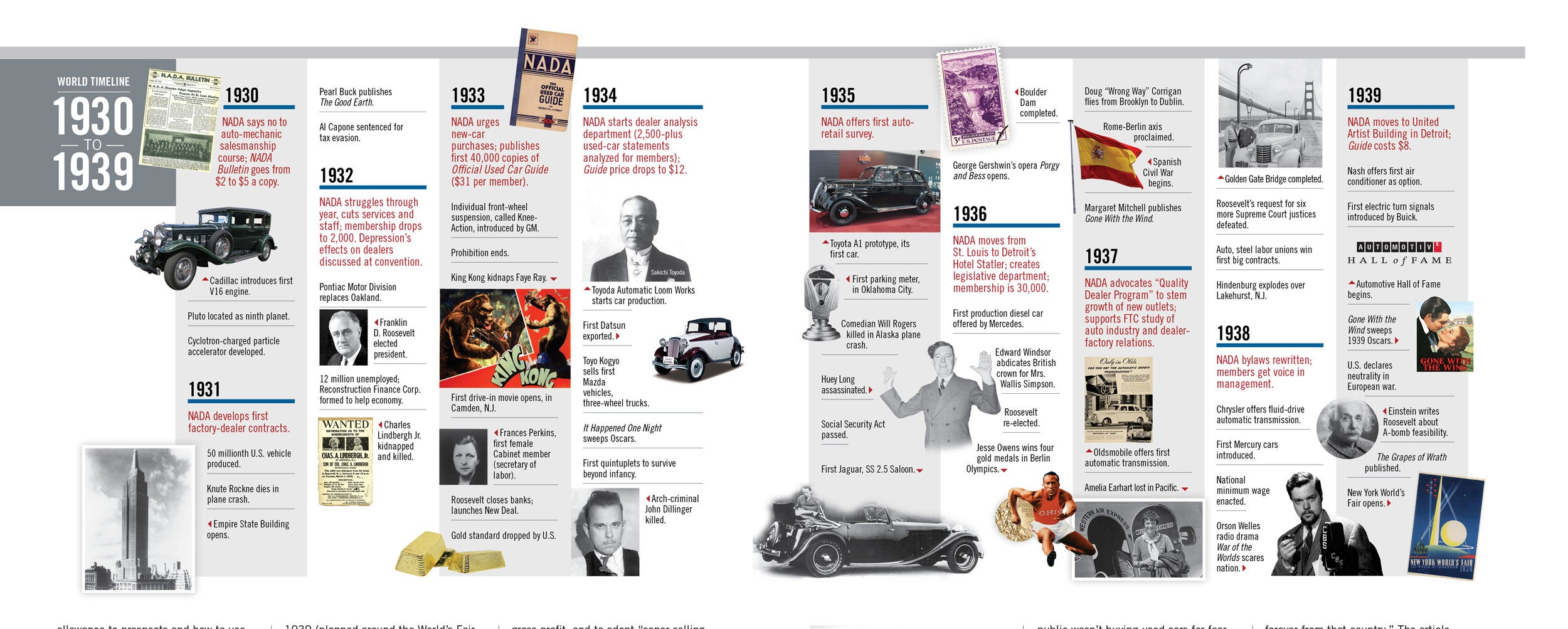

1930s: The Depression Years

NADA almost didn’t survive the Great Depression. The first four months of 1932 left the association—after expenses of $20,879—with a net income of $837. In May, NADA’s general manager told the board that, based on the renewal record and members’ difficulty in paying dues, it would be “impossible to carry the association beyond the first six months of the year without drastic changes.”

The secretary was to find new quarters for the association at a cost not to exceed $50 per month. The board reduced activity to a minimum and for the rest of 1932 employed only a secretary-manager and a stenographer, who also handled bookkeeping. The general counsel, field staff and mailroom clerk were let go.

But a year later, things were different. In February 1933, NADA had 2,200 members, most of whom were behind in their dues. But by early 1934, NADA had an active, paid-up membership of more than 20,000. By the end of the year, there were 30,000. A motor magazine editor speaking at the 1934 convention said, “It is incredible that so infinite an improvement could have been recorded in so short a space. For the average dealer who had lived so close to the gates of hell that he could smell the sulphur, the swiftly changing scene has brought a glimpse of a business paradise to which he may aspire....Our grandchildren, reading their histories, will have a clearer conception than we of the swift sequence of portentous events which have crowded the past 11 months.”

The New Deal

The turnaround was the result of the New Deal’s National Recovery Administration and the new Code of Fair Competition for the Motor Vehicle Retailing Trade. When the mandate of industry-specific codes was announced, the nearly dissolved association went into a flurry of activity, developing a proposed code and visiting dealers around the country for suggestions and support.

Factory relations and dealer profitability were pressing topics throughout the 1930s. And until Prohibition ended in 1933, NADA lobbied on behalf of dealers who suffered losses when cars on which they held unpaid liens were confiscated by the Revenue Department because the owners had violated liquor laws. NADA also launched a publicity campaign urging customers to buy new cars.

In 1935, NADA announced a Speakers’ Bureau Service to help state and local dealer associations obtain lists of speakers who could address dealer groups for free. NADA also began regular, confidential studies—sales of new cars and equipment, used cars, reconditioning, parts and equipment, service, income tax, advertising—to define and quantify dealers’ problems. A survey of 359 dealers at the time showed an average gross profit per new-car sale of $171.87 (20 percent); direct expense of $89.09 per sale; indirect expense of $34.45; and an operating profit of $48.33 on a unit sales average of $853.17. These surveys continue in various forms today.

A Focus on Legislation

When NADA moved to Detroit in December 1936, it formed a new legislative department, prepared a Standard Used Car Appraisal Form, and began a dealer education program to demonstrate how to sell the used-car allowance to prospects and how to use the Guide. Dealer count, which had dropped to a low of 35,265 in 1933, was up to 41,992 in 1938. A 1939 article headline decried, “Too Many Dealers; What Can Be Done About It?”

For the 22nd convention in April 1939 (planned around the World’s Fair and Golden Gate Exposition), a special train was arranged to take dealers from Chicago to San Francisco. And for the 1940 convention in Pittsburgh, NADA invited Eastern dealers to travel to Pittsburgh via “The Dream Highway,” the new Pennsylvania Turnpike.

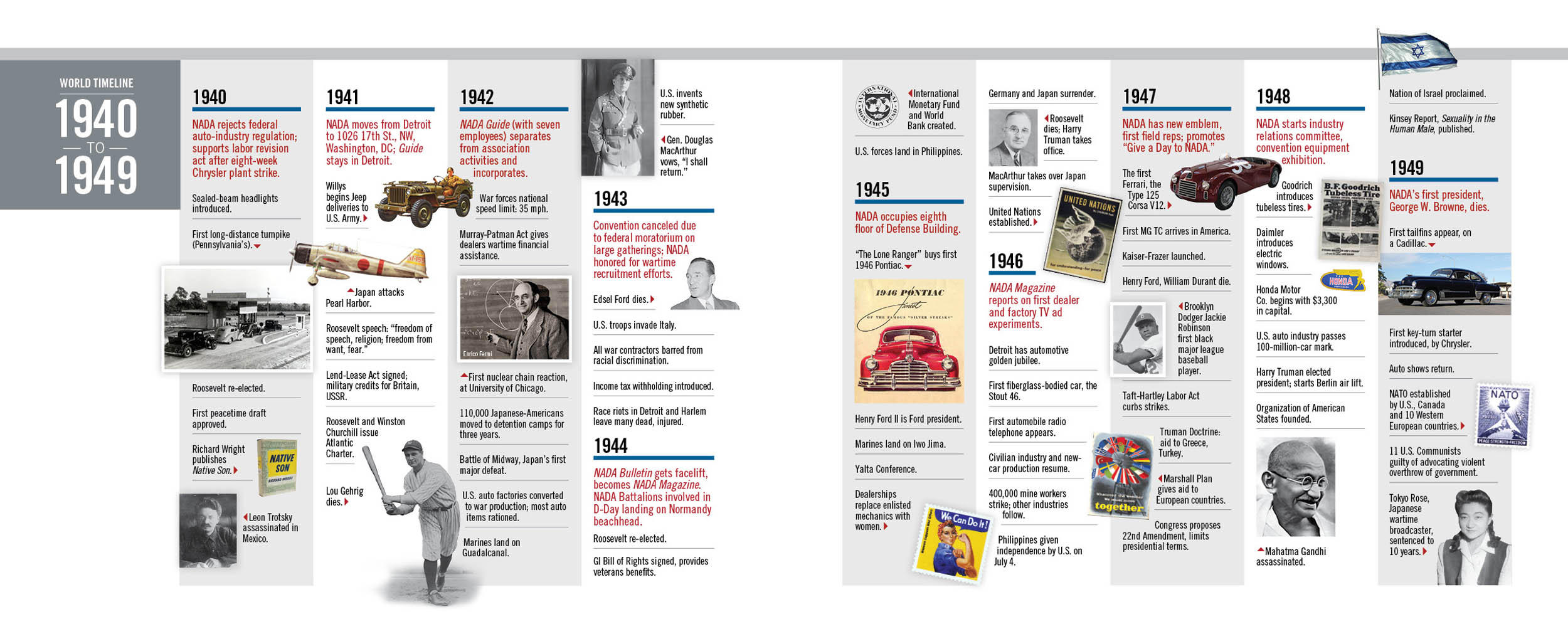

1940s: NADA and WWII

In 1941, NADA moved from Detroit to Washington, D.C., to work more closely with government agencies and keep tabs on legislative events. NADA also worked with automakers to obtain many changes in factory policy favorable to dealers.

In those early war years, NADA bulletins urged members to be more profit-conscious, to work on improving gross profit, and to adopt “saner selling methods” to prepare for higher taxes and higher costs of doing business. And through prepared newspaper articles, NADA tried to show the public the importance of cars to the economy.

The 1942 convention marked NADA’s 25th anniversary, and 2,300 dealers attended. With American’s entry into WWII, the talk was of survival, the threat of gas rationing and the government freeze on vehicle delivery. A March 1942 Census Bureau report of 23 common types of businesses showed that dealers were by far the hardest hit by the war program. NADA lobbied Congress to minimize the effects of rationing and other war-related restrictions.

Orders Grind to a Halt

It was a tough year for dealers. The public wasn’t buying used cars for fear that the government would appropriate them; dealers were reluctant to acquire used cars because of rumors that their inventories would be frozen. Uncle Sam had already prohibited the sale and delivery of new cars and trucks; only customers who had placed orders before Jan. 1, 1942, could take delivery of new cars. Business was further eroded by nationwide gas rationing.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt brought relief to struggling dealers, signing into law a measure allowing them to sell to the government new cars and trucks that had been subject to rationing.

NADA’s January 1942 newsletter warned that “the war with Japan may eliminate the American automobile forever from that country.” The article noted that business had been on the “downgrade” for several years and that the last foreign manufacturer was considering moving its plant out when the war broke out. And, it said prophetically, Japan already produces beyond its own “small” requirements.

Dealer service business took a hit when the Army asked NADA to help recruit mechanics in 1942-1943 in so-called NADA Battalions overseas. The 950 officers and 26,000 enlisted men saw action in Tunisia, Italy and Germany, and in the D-Day landing on the Normandy beachhead. Their mechanical skills were credited with keeping the wheels of war rolling, and NADA was honored for its part in recruitment.

Women Fill the Gaps

With dealership service departments experiencing a crippling personnel drain, dealers turned to women. One NADA dealer reported that 45 women responded to his newspaper ad for one service technician. “They ranged from high school girls to gray-haired grandmothers. They came in fur coats and in sweaters and slacks. Some even came with infants in arms,” he wrote.

The Office of Price Administration (OPA) advised civilians to put off unnecessary repairs such as bent fenders and crumpled radiators and encouraged them to keep cars longer. And it took increasing resourcefulness for dealers to stay in business. One Indiana dealer bought radios, refrigerators, freezers and furnaces to sell in his showroom, and then sold toys at Christmas. Amazingly, a postwar NADA survey showed that 85 percent of dealers managed to stay afloat.

The 1943 convention was canceled because of a government ban on assemblies larger than 50 people. A scaled-back convention was held in 1944, but because of wartime “congestion” in Detroit, dealers had to share hotel rooms. Henry Ford II addressed conventioneers that year, the first Ford family member to do so. As the war continued, the next two conventions were canceled.

Highway Funds to the Rescue

But Roosevelt’s proposed $15 billion highway project provided impetus for NADA, which actively supported the measure, along with numerous safety campaigns to combat rising highway deaths over the next two decades.

By 1944, civilians had to apply to the federal government to buy one of the nation’s remaining 60,000 new cars. Washington announced that no new cars could be built until the war was over and turned its attention to used cars. NADA lobbied vigorously against rationing and price ceilings for used vehicles, warning that they were creating a black market and destroying dealers’ one remaining source of business. The Guide adapted its format to include both average prices and OPA ceilings. With used vehicles assuming more importance during and immediately after the war, Guide subscriptions leaped from 28,000 in 1945 to 50,000 one year later.

NADA membership, which had taken a big hit during the war, also skyrocketed, thanks to a massive membership drive. By 1949, membership would be 35,000.

After the war, automobile production resumed. But waiting lists of two years for a new car were not uncommon, and NADA expanded its public relations staff to help counter the public perception that dealers were getting rich off the shortage. NADA urged its members to be responsible, distributing a pamphlet, The Truth About the Current Automobile Situation, to diffuse public ill will.

The first postwar convention in 1947 was also NADA’s 30th, and a record 6,500 attendees traveled to Atlantic City, N.J. The resumption of local auto shows in 1949 signaled that life was back to normal.

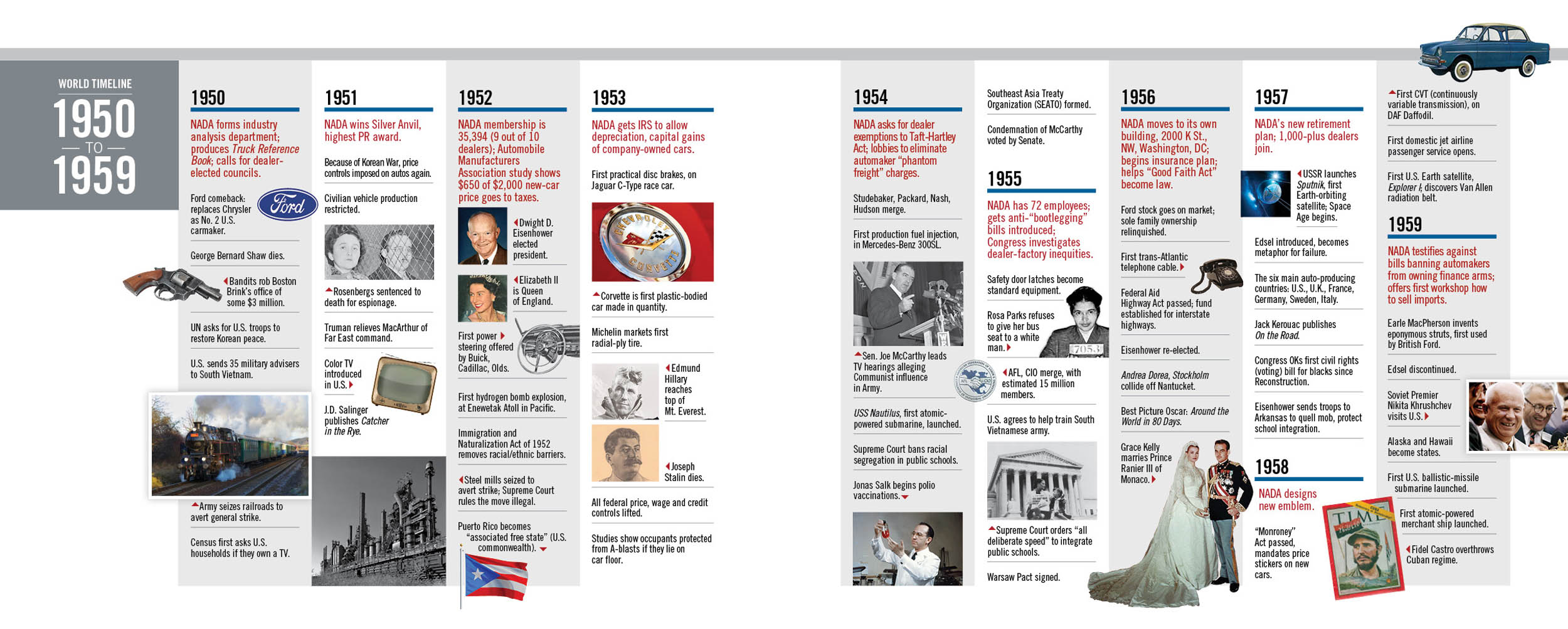

1950s: Dealer-Automaker Relations

After the war, the auto industry discovered television. NADA predicted that, based on initial experiments with dealer and factory TV ads, the medium would become “a permanent sales tool of the automotive industry.” Radio also became increasingly important during this decade. NADA provided dealers with free five-minute public interest scripts for local radio broadcasts.

As the nation remobilized for the Korean War, dealers braced for another halt in car production. Price controls were again slapped on the auto industry. To help pay for rearmament, Congress imposed a 7 percent excise tax on new cars, which NADA criticized for pushing the average price of a car to $2,200. Although the association fought for its repeal after the war, the tax was not lifted and was later raised to 10 percent. As it had done in 1917, NADA countered with a public relations campaign stressing the “essentiality” of the car to the American way of life and the inconsistency of taxing cars but not luxury items such as yachts.

Washington also restricted automakers’ steel supply, causing them to close plants and lay off workers. When the government set 1952 production levels for individual automakers, there were still 11 players in the field—GM, Chrysler, Ford, Studebaker, Nash, Hudson, Packard, Kaiser-Frazer, Willys, Crosley and Checker.

Code of Ethics

Meanwhile, NADA started a campaign urging dealers to adopt a code of ethics. An NADA survey showed the public didn’t trust dealers, thought their profits were too high and took their cars elsewhere for service. NADA countered with studies showing that dealers made less profit than plumbers and bakers.

Dealer-manufacturer relations suffered during the deep recession of the early 1950s. Manufacturers tried to buoy auto sales with drastic measures, which drove many dealers out of business. With NADA’s full support, dealers finally appealed to Congress to mandate fair play, and Congress recognized the manufacturers’ abuse of the disparate bargaining ability of dealers. The Dealer’s Day in Court Law of 1956 allowed dealers to bring suit against an automobile manufacturer and recover damages for the manufacturer’s failure to “act in good faith in performing or complying with any of the terms or provisions of the franchise.”

After the Korean War, employment in the United States was at an all-time high. Detroit set production records, and for the first time, dealers worried about too much of a good thing. One NADA official called the specter of overcapacity “an automotive hydrogen bomb that hangs poised over all dealerships.” In a prophetic statement, 1952 NADA President J. Saxton Lloyd said it was unfair to dealers “to be forced to absorb or dispose of so many more cars than the public will buy that we all have to give them away at practically no profit or perhaps at a loss.”

Restoring Consumer Faith

NADA helped draft the Price Labeling Law in 1958, which mandated window stickers listing manufacturer suggested retail prices for cars and all options, accessories, handling, freight and federal taxes. The Monroney sticker, named for Sen. Mike Monroney (D-Okla.), father of the law, helped restore consumer faith in the auto industry and transformed the car-buying process.

NADA sought improvements in dealer-automaker relations, and lobbied Congress for repeal of the 10 percent excise tax on new cars, and reinstatement of depreciation and capital gains tax treatment of company vehicles, which had been disallowed by the IRS in 1948. NADA formalized ties with local and state dealer associations, built an eight-story building in the nation’s capital, and started a nationwide workshop program, a truck advisory committee, and a retirement plan for dealers and their families. NADA was also active in various public service programs, including a national, nonpartisan get-out-the-vote campaign, highway safety programs and the loaning of cars to high schools’ newly created driver education classes.

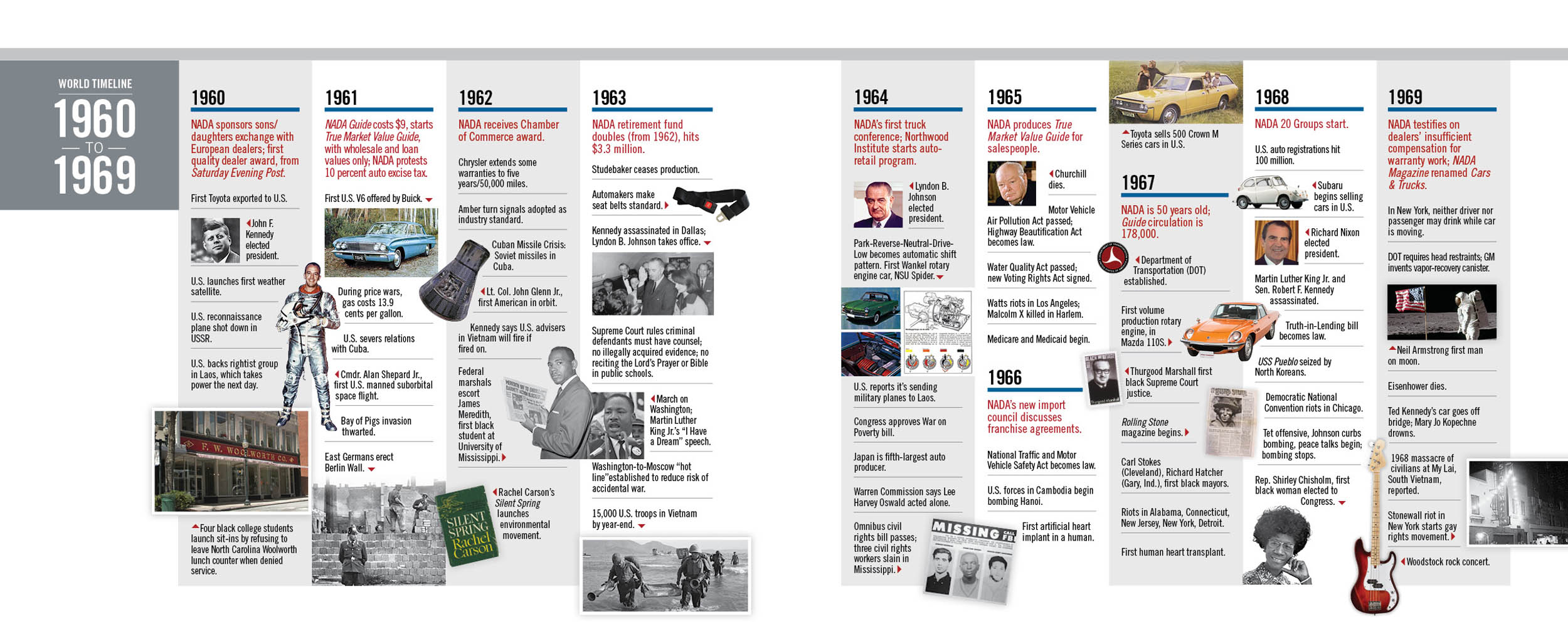

1960s: The Imports Arrive

At the end of the 1950s, there were six main car-producing countries in the world: the United States, England, France, Germany, Sweden and Italy. The top 10 import lines were VW, Renault, Opel, English Ford, Fiat, Triumph, Simca, Austin Healey, Mercedes and Volvo.

By the early 1960s, Japan entered the competition and swiftly grew to the world’s fifth-largest auto producer. Toyota introduced its first model—the Toyopet—to the U.S. market, while Honda initially sold only scooters and then built the Civic. Mazda and Datsun (later Nissan) also joined in. At the same time, U.S. automakers saw sales slip, while other OEMs folded, including Studebaker in 1963.

Sweeping national safety laws affected everything from car design to showroom floor sales tactics, and the first federal bills to set limits on vehicle emissions were introduced in 1965. California was the first locality to require “anti-smog equipment” on cars, and the nation eventually followed suit.

20 Group Program Launched

In 1968, NADA started its 20 Group program, and Frank McCarthy began what would be a 33-year stint at NADA, first as executive vice president, then as president. McCarthy would spearhead key programs, such as retirement and insurance for dealers and their employees, as well as management training for dealers and political action efforts.

NADA also spent a good deal of time in the late 1960s and 1970s testifying before Congress or federal agencies about various proposals. When proposals became law—such as the Truth in Lending law of 1968—or regulations, the NADA staff worked to explain the new laws and regulatory actions to dealers.

Other legislation that NADA favorably influenced during the 1960s included a bill for licensing mechanics, which NADA fended off with a proposal to set up its own licensing program instead, and a bill that protected dealers against federal tax liens on vehicles taken in trade or purchased outright.

And in a foreshadowing of recall difficulties that would plague the industry in coming decades, NADA testified before the Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly, encouraging clarity in manufacturer warranties, which helped alleviate dealer-customer friction over manufacturer defects.

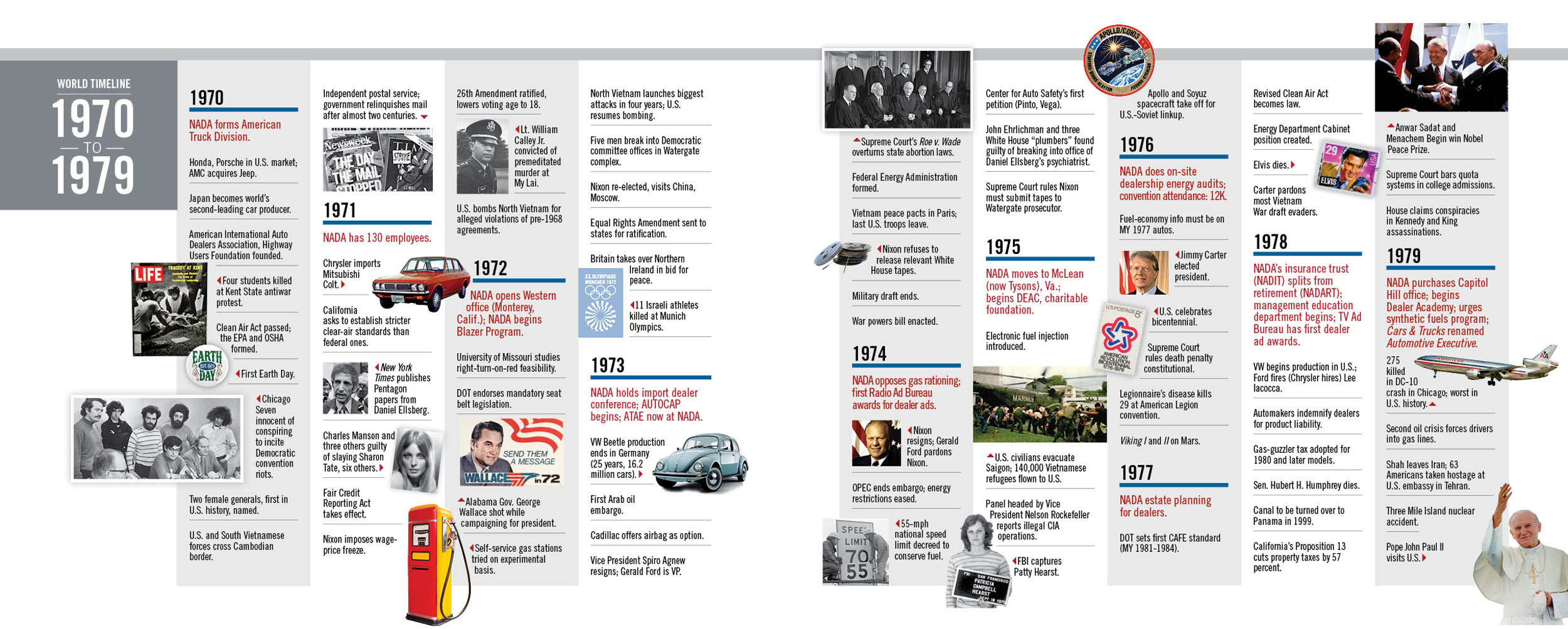

1970s: New NADA Initiatives

With the increase in imports, trade became an issue in Congress and elsewhere. In 1970, NADA went on record opposing a trade bill that would have imposed quotas if imports reached a certain percentage of the market.

But the 1970 Clean Air Act and the 1973 energy crisis had the greatest effects on car sales. By 1974, sales of midsized cars were so poor that NADA ran ads to promote them. NADA supported voluntary energy conservation measures, rather than mandatory ones such as gas taxes and rationing. Nonetheless, CAFE (corporate average fuel economy) standards were first set in 1977, and a gas-guzzler tax was passed the next year.

One piece of NADA-backed legislation that benefited consumers and dealers alike was the anti-odometer tampering amendment of 1972, which prohibited the sale of devices that could change the odometer mileage and operation of vehicles with disconnected odometers. In 1986, NADA worked for the passage of another odometer law requiring a record of a vehicle’s mileage when it changed owners.

While it may seem quaint now, the association promoted a dealership image campaign with the NADA Blazer Program in 1972. Many automakers were encouraging dealers to buy blazers for their employees. Through NADA, dealers could buy hopsack blazers for $26 or double-knit polyester for $30.

New NADA Divisions Launched

By 1975, NADA had outgrown its building in downtown Washington, D.C., and moved to its current headquarters in suburban Virginia. That same year, the Dealers Election Action Committee (DEAC) began. In 1976, the group’s first full year, dealers contributed more than $1 million. (DEAC was renamed NADA PAC last year.)

Also in 1975, the National Automobile Dealers Charitable Foundation (NADCF) was formed, with an outreach campaign to dealers in 1977. Two years later, the foundation delivered more than 50 grants under its Emergency Medical Services program, which provides Resusci Anne CPR training units to organizations in 50 states. An Ambassadors Program and various memorial funds were added later. (NADCF was renamed the NADA Foundation last year.)

In 1978, NADA launched a national campaign to build public support for automobiles and counter efforts to restrict their use because of gas shortages and emissions concerns. Financed by NADA members and the Big Three, the campaign gave its first annual International Freedom of Mobility award to Barry Bruce-Biggs, author of The War Against the Automobile. In 1979, the Automobility Campaign initiated “You Can If You Plan,” an advertising campaign informing consumers how to plan ahead to cope with fuel shortages. Also part of the campaign: America's Automobile Man, a vinyl record produced, with the lyrics: “He's keepin’ America movin’, keepin’ America strong. Providing the wheels to the future, helpin’ our world move along.”

NADA Data Published

Though NADA had previously published economic facts and figures on the economic impact of new-car and -truck dealers, the association published its first edition of NADA Data in 1979. The annual report quickly became a popular mainstay for analysts, the media and other industry watchers, and helped spawn monthly reports on dealership financial profiles and sales trends.

Several NADA divisions and initiatives were added during the decade. This included the American Truck Dealers Division (1970), the industry relations department (mid-1970s) to work with automakers, and the NADA Legal Defense Fund (1975) to provide financial and legal assistance.

The continuing education division (1978) published its first management guides for dealers and was renamed management education in 1983. And the Dealer Academy was launched in 1979, the same year NADA’s legislative staff moved to an NADA-owned building just two blocks from the U.S. Capitol.

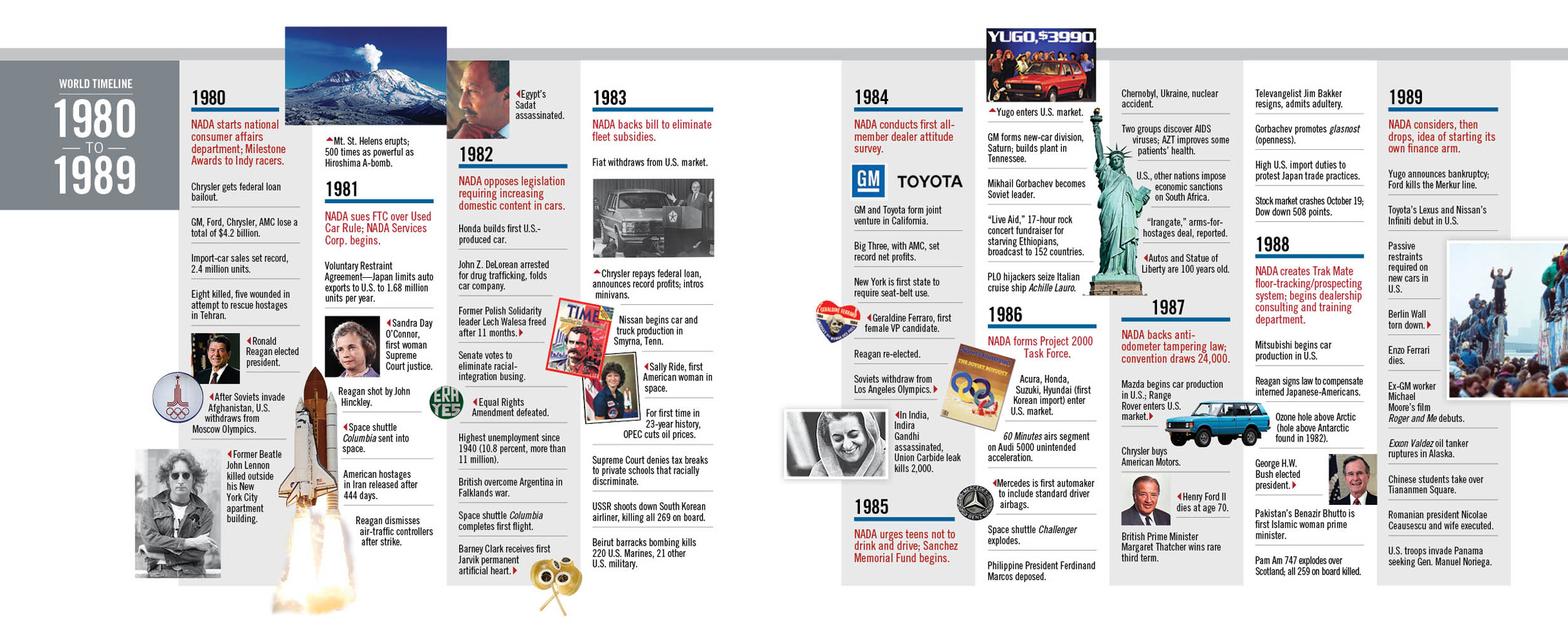

1980s: Emergency Measures

By 1979, with sky-high interest rates and double-digit inflation, car dealers were in real trouble. NADA urged President Carter to decontrol oil prices and sought emergency measures from automakers, such as 30-day floorplan assistance and cash incentives to dealers for slow-moving models to help with cash flow problems caused by bloated inventories.

In 1980, NADA asked Carter to take action to stimulate new-car and -truck sales. Responding to NADA proposals, Carter increased the Small Business Administration loan guarantee fund for car and truck dealers so that 95 percent of dealers were eligible.

In 1984, NADA conducted its first dealer attitude survey, where dealers rated automakers on such criteria as OEM interaction and policies. The semiannual surveys soon grew in influence, from a curiosity to automaker CEOs meeting directly with dealers and NADA to discuss the results.

Regulatory Headaches

After one of the most convoluted rulemaking odysseys in modern history, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued a rule requiring dealers to post a sticker on used cars telling customers whether the car came “as is” or with a warranty, along with other information. The first federal version was proposed in 1976, and NADA fought mandated inspections and warranties for five years as “nebulous, ambiguous, and unworkable.” After NADA sued the FTC, a toned-down version of the rule was issued in 1984, without the provisions for mandated inspection and disclosure of condition of more than 50 components and a history of who previously owned the car and how it was used.

At the 1986 NADA convention, incoming president Jim Woulfe announced Project 2000, a blue-ribbon panel to study the future of the franchise system. The task force received input from dealers, ATAEs and others to look at franchise agreements, customer satisfaction, employee training and retention, dealer-manufacturer communications, computer technology and data. The Project 2000 committee issued various reports on industry trends to help dealers plan for the future.

For the most part, the 1980s saw dealers caught up in the problems facing a wide range of businesses brought about by concern over the disposal and cleanup of hazardous waste, disposition of leaking underground storage tanks, money-laundering rules that required reporting of cash transactions greater than $10,000, and never-ending tax battles. But most of the Washington activity directed at dealers revolved around defining regulations.

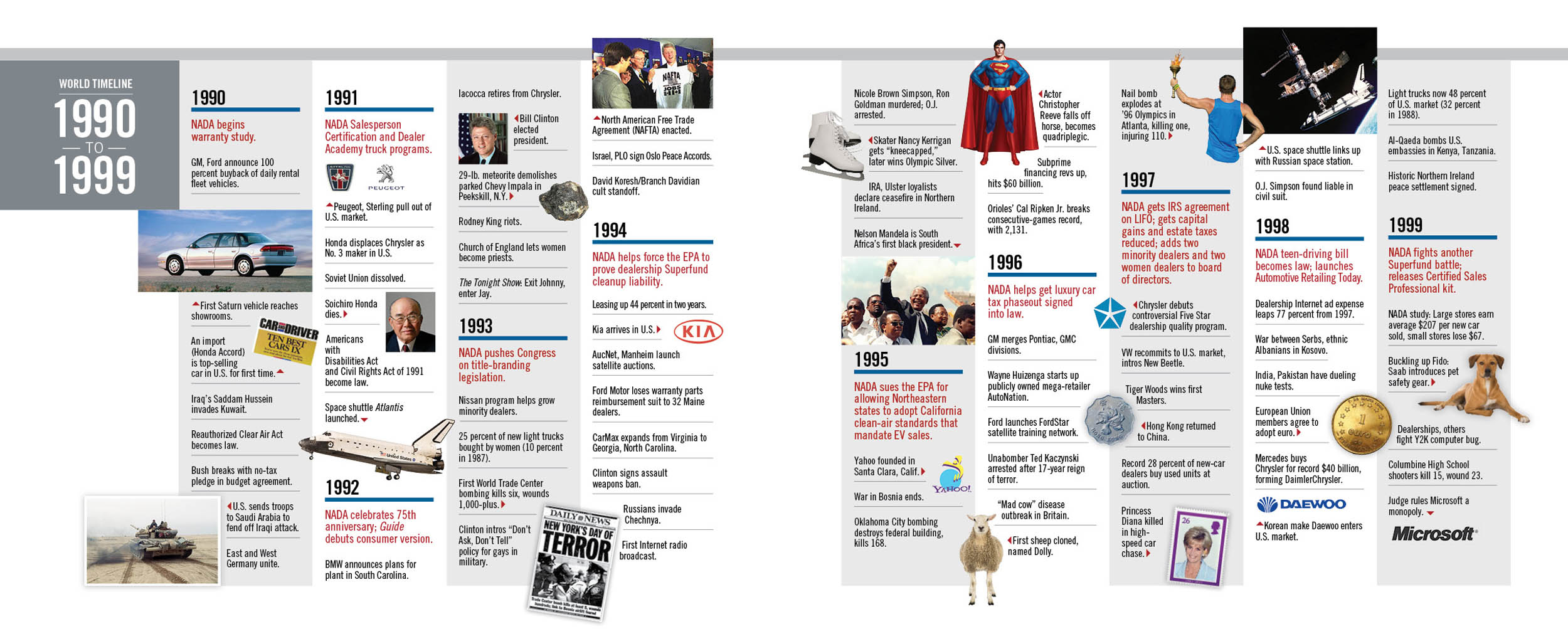

1990s: A New Millenium

Many of these same issues continued into the 1990s. There were new rules for the Clean Air Act, including higher proposed CAFE standards. NADA sued the EPA on its ozone standards and for allowing Northeastern states to adopt California clean-air standards. The EPA stepped up enforcement of Superfund—passed in 1980—with its “cradle-to-grave” liability for improperly disposed used oil.

On the labor front, NADA worked with Congress on the Americans with Disabilities Act before it became law, then informed dealers of their legal requirements. With the AIDS epidemic in full force, NADA published guidelines to help dealers establish effective workplace policies and educational programs to help employees better understand the disease.

NADA also advocated for title-branding bills for salvage vehicles, because both dealers and consumers had been unwitting purchasers of these units. And NADA was successful in reducing the federal excise tax on heavy-duty trucks.

Tax Battles Continue

At the same time, the issue that led to the creation of NADA in 1917 was back in 1990 with a luxury tax enacted on vehicles retailing for more than $32,500. Despite long odds, NADA scored a huge victory in 1996 with a phaseout of the tax. NADA leaders were even invited by President Bill Clinton to a signing ceremony on the White House lawn.

On the manufacturer side, fleet subsidies—or “program cars” from rental car companies—were flooding the market. NADA’s efforts led to important changes in these programs. And factory relations were not so smooth on other fronts, with NADA battling mandatory binding arbitration provisions and factory image campaigns. NADA also created a special task force to study the long-term consequences of automaker programs that reduced dealer profitability.

Diversity became more prominent during the decade, with various automakers promoting programs to boost the number of minority dealers. NADA added four new at-large members—two minorities and two women—to its board of directors in 1998. A few years later, NADA began two all-minority 20 Group programs and hosted a diversity forum for dealers and automakers. (And in 2005, the association began the first annual women dealers event at its convention.)

Defending the Dealer Image

Later in 1998, NADA and a coalition of automakers formed Automotive Retailing Today (ART) to improve the way the public and the media view the auto industry in general and dealers in particular. With various hidden-camera TV reports unfairly attacking dealers earlier in the decade, NADA had already launched a sales certification program to address image problems and chronic salesperson turnover. NADA also began a “Stomp and Steer” PR campaign with four-time Indianapolis 500 winner Al Unser on how to use anti-lock braking systems.

By the end of the decade, some of the more high-profile priorities for dealers were the public dealer groups (Republic, Lithia, United Auto Group and others), dealer consolidation, the Internet and the millennium madness called Y2K.

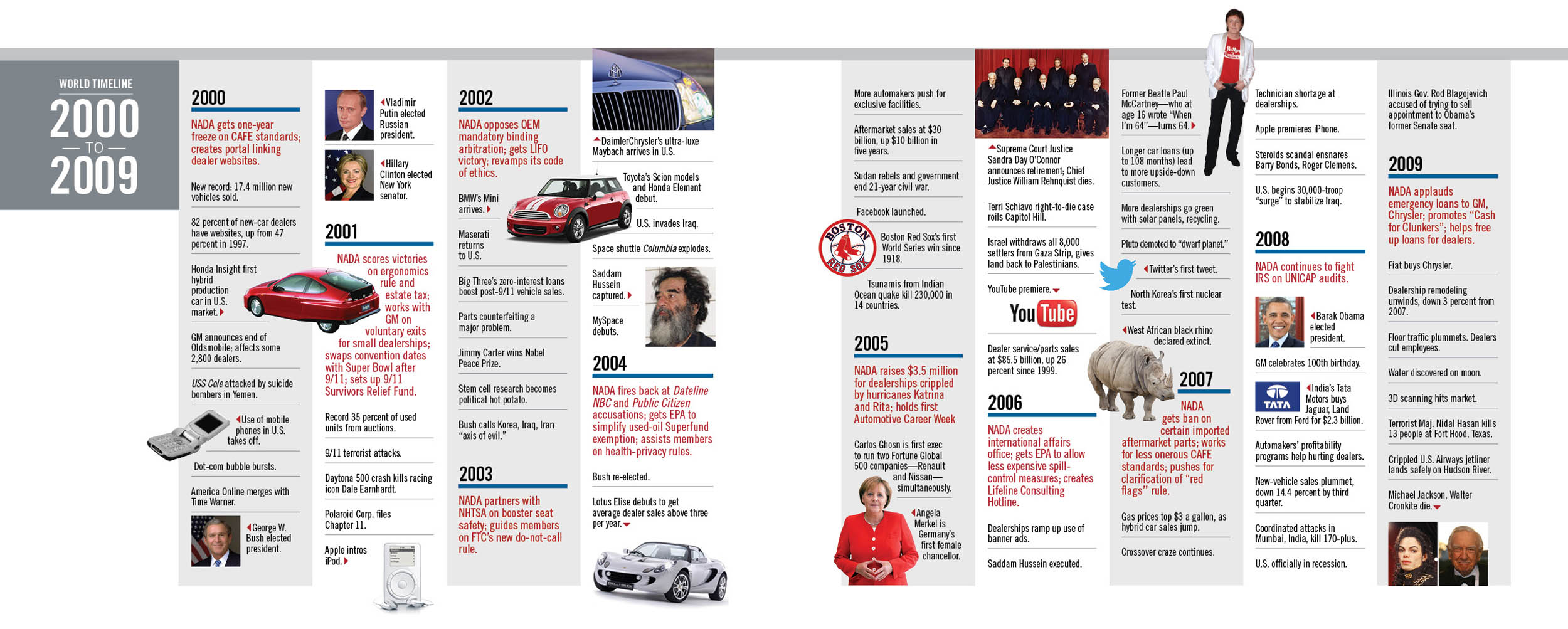

2000s: Decade of Uncertainty

From 9/11 to 2010, the decade was full of change and challenges. Yet the 2000s began calmly enough, with no Y2K meltdown of the world’s computers. Soon dealers faced success on many fronts. OSHA proposed sweeping new ergonomics standards, which were soon overturned by Congress. An NADA-backed bill lowering the estate tax (for one year) would soon be signed into law by President George W. Bush.

Ford and GM wanted to sell directly to consumers, but those plans—which included the OEMs selling cars online—were quashed by state legislation. NADA then created a national portal to link dealer websites. While Ford’s Blue Oval and other dealer performance programs became a concern, NADA opposed automaker efforts to impose unfair burdens on dealers.

But Oldsmobile was shuttered in late 2000, following sagging sales, so NADA pushed GM for just compensation, as well as low- or no-cost loans and floorplanning assistance from GMAC. Then longtime NADA chief Frank E. McCarthy died a few months later. After a nationwide search, Phillip D. Brady became NADA president, and September 10, 2001, there was a dedication ceremony to name NADA headquarters the Frank E. McCarthy Building.

Terrorists Strike

NADA was in the midst of its 26th annual Washington Conference the next day when terrorists struck the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. With uncertainty after the 9/11 attacks and airports closed, many dealers and NADA staff hunkered down for days at the Capital Hilton in Washington, D.C.

The National Automobile Dealers Charitable Foundation quickly established a survivors’ relief fund to help meet the educational needs of the victims’ dependents. The attacks meant the Super Bowl would be delayed by one week, which caused a scheduling conflict with the NADA Convention in New Orleans. As part of a “Super Bowl swap,” NADA agreed to move up its convention, which required extensive last-minute maneuvering with attendees who already had made their plans, as well as speakers, exhibitors, hotels and the convention center.

Despite the shock of the attacks, NADA moved forward, achieving a major victory when voluntary arbitration in franchise agreements became law in 2002. The association created a code of ethics to help dealers run their businesses, partnered with USA Today on a Dealer Innovation Award to recognize technology-savvy dealers, and teamed with NHTSA to promote child safety-seat events at dealerships.

Initiatives to Support Dealers

By 2004, NADA was tackling poorly constructed automaker CSI programs, then promoting initiatives to help the media and consumers better understand the benefits of dealer-assisted financing. NADA became a founding member of AWARE (Americans Well-Informed about Automotive Retailing Economics) and joined with Junior Achievement to teach middle-school students about personal finance.

The association wanted to bolster dealers in other ways, so it introduced the NADA Century Award (page 56), honoring dealerships that have been in the transportation business for 100 years or more. To foster dealership job opportunities, NADA developed a tool kit for dealers to promote automotive careers, helped former NCAA student athletes find jobs and promoted AYES—Automotive Youth Education Systems—to recruit service techs. NADA also worked with Energy Star and promoted “green” dealerships to help dealers cut utility and other costs, then started a green checkup campaign for dealerships to show consumers how to reduce their carbon footprint.

When Hurricane Katrina and later Rita smashed into the Gulf Coast in 2005, NADA helped dealership employees by distributing more than $4 million through the Emergency Relief Fund. Three years later, the National Automobile Dealers Charitable Foundation presented a $400,000 check to the Lusher Charter School in New Orleans to restore acres of athletic fields damaged by Hurricane Katrina. In 2009, the association held its convention in New Orleans, the first time since the hurricanes, with former presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, who together had spearheaded critical relief efforts for the area.

The Great Recession

For years, NADA had been pushing for total-loss disclosure on vehicles that had been totaled, stolen or damaged by flood. The 2005 hurricanes were the unfortunate catalyst for trying to move this legislation forward. Along with vehicle identification, there was now a consumer-identification issue after the FTC issued “red flags” rules to prevent identity theft.

But another storm was brewing, though this one was financial. The Great Recession officially began in late 2007, though many dealers had already been struggling for years. NADA launched a Performance Improvement Program (PIP) and “Lifeline to Profit$” consulting hotline in response. When the health of thousands of GM and Chrysler dealerships was threatened in 2008, NADA organized multiple fly-ins to Washington to influence Congress on auto-industry relief bills and held dealership-survival workshops at the 2009 convention.

An NADA Industry Stabilization Task Force was formed to encourage the government to act quickly to stimulate the economy. This included bridge loans for Chrysler and GM, as well as expanded SBA loan guarantees and a “Cash for Clunkers” program to bolster new-car sales. NADA leadership testified before Congress and met with regulators and White House staff.

While many dealerships were saved, some were not. And it would take many more years for dealers and the country to truly find their financial footing.

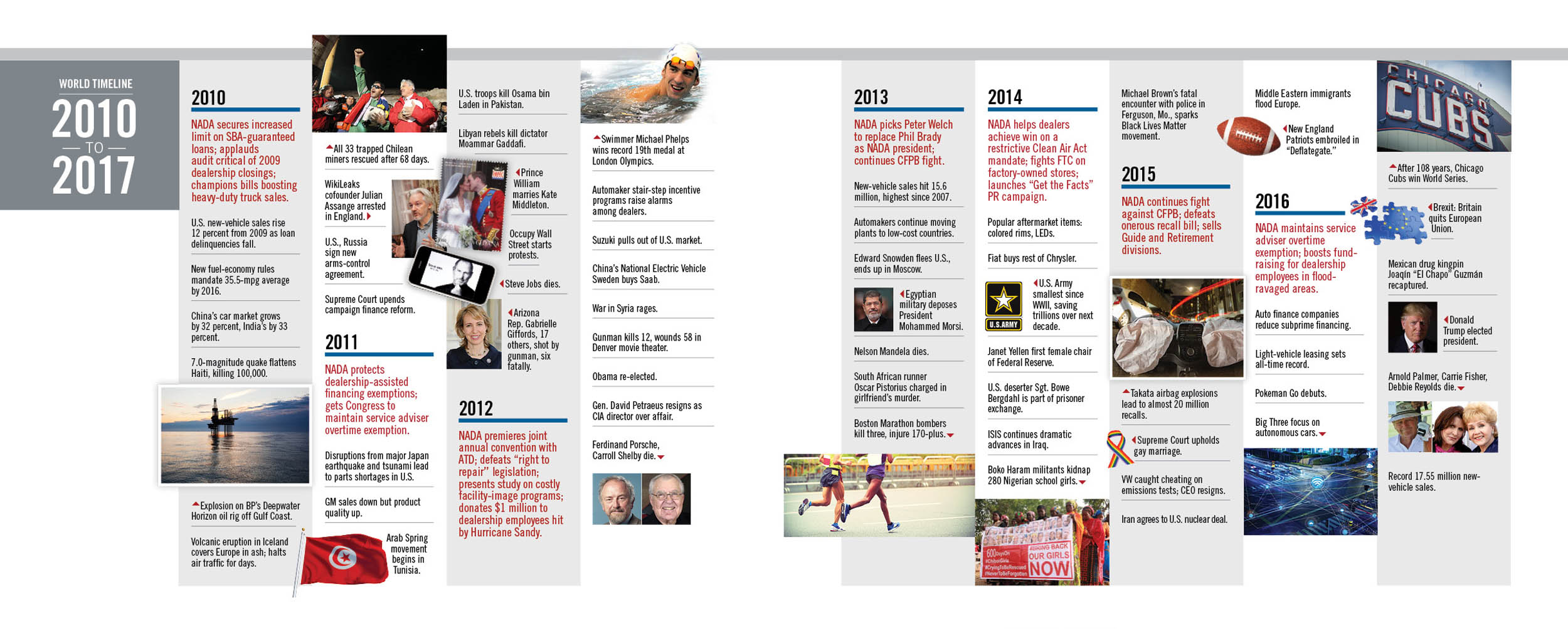

2010s: Bouncing Back

In early 2010, as part of financial reform legislation passed after the Great Recession, NADA strongly supported an amendment protecting dealer-assisted financing from further regulation. As a result, Congress soon passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which excluded dealers from the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).

But the next year, NADA had to defend dealer-assisted financing during a series of Federal Trade Commission roundtables. Despite the forums being stacked against dealers, no new regulations resulted from these roundtables.

Fair Credit Law Compliance

In 2013, the CFPB pressured auto-finance sources to change how they compensated dealers for arranging financing, which NADA and the National Association of Minority Dealers (NAMAD) argued would end the consumer’s ability to negotiate a discounted interest rate. A number of legislators agreed, repeatedly asking the CFPB for more information, which the agency never fully provided. NADA continued to pressure the CFPB on its methodology. NADA—along with the American International Automobile Dealers Association and NAMAD—also released the Fair Credit Compliance Policy and Program to help strengthen a dealership’s efforts to comply with fair-credit laws.

NADA also supported its recession-battered members in other ways, with favorable action on SBA-guaranteed loans, stabilizing the estate tax, preserving LIFO and other issues. NADA helped defeat “right to repair” legislation—a push by aftermarket manufacturers to obtain OEM proprietary data—as well as an amendment in a federal highway bill in 2015 prohibiting dealers from selling or wholesaling used vehicles under open recall.

NADA went to the mat over CAFE, noting how proposed new fuel-economy mandates would increase vehicle prices and force 6.8 million buyers out of the market. NADA pushed for legislation to address the increase in costs caused by duplicative fuel-economy regulations from NHTSA, the EPA and the state of California, and short-circuited a government plan that would have required dealers to fund an electric vehicle tax credit, then seek reimbursement from the IRS.

To foster good relations with Capitol Hill, NADA reached out to regulators and legislators by inviting them to various NADA committee meetings each year.

New Events Launched for Dealers

Also during the 2010s, NADA hosted its first annual Auto Forum NY, with dealers, automakers, analysts and other industry experts discussing the latest economic trends affecting the business. NADA then began what is now the Auto Conference LA, with a special focus on the California marketplace.

Phil Brady, then NADA president, left the association in 2012 and was replaced by Peter K. Welch, who had been president and CEO of the California New Car Dealers Association since 2003. Welch is now also NADA CEO.

To help streamline operations, NADA sold its retirement division and Used Car Guide in 2015. NADA also began a major rebranding, with new logos for NADA and ATD. The next year, after a nine-year comeback from the Great Recession, new-vehicle sales hit a record 17.55 million.

Moving forward

In 2017, NADA launched “NADA100,” a yearlong celebration of its 100th anniversary, at its annual show in New Orleans.

NADA is always looking to the future, and that is especially true as the association turns the corner on its first 100 years. A recent study, The Dealership of Tomorrow: 2025, was prepared for NADA to look at retail auto-industry trends. The forecast is bright for dealers, showing how their businesses will remain the dominant way vehicles are sold and serviced.

Yet there will be plenty of changes down the road, especially with digital dealerships and autonomous and electric vehicles on the horizon. But as the past century has shown—from world wars and recessions to onboard diagnostics and mobile apps— dealers certainly know how to adapt.